Introduction

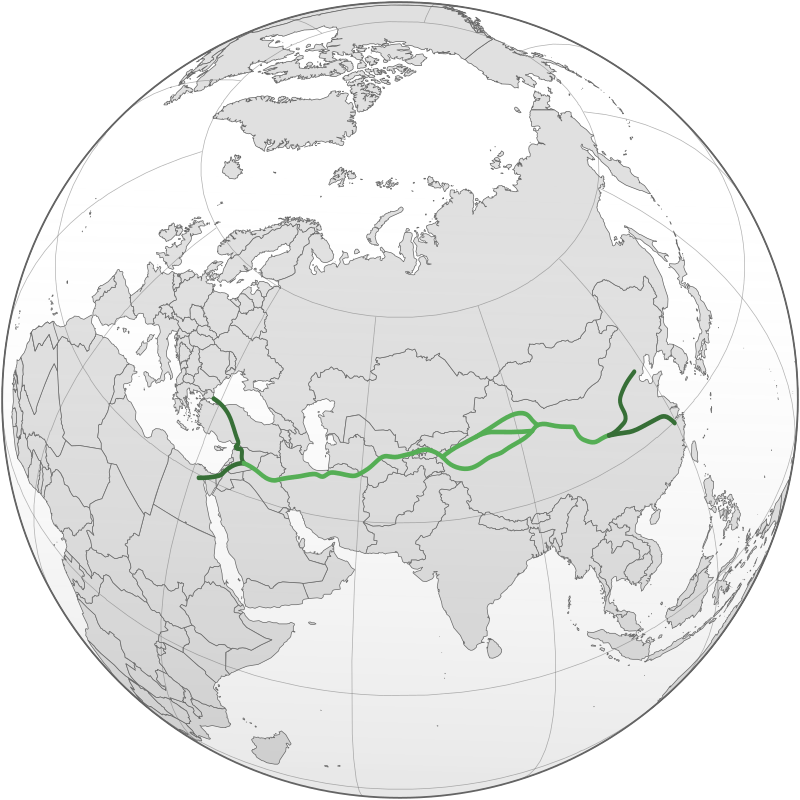

The Silk Road, spanning the vast Asian continent, holds a unique position in human history as a symbol of cultural exchange, economic development, and the spread of ideas across Asia, Europe, and Africa. For over 2,000 years, this intricate network of land and sea trade routes connected China to distant regions such as Korea, Japan, India, Turkey, and Italy. The Silk Road was more than just a physical path; it was a conduit for the movement of highly sought-after commodities like silk, spices, and precious metals, as well as a vehicle for the exchange of knowledge, art, and culture. This essay delves into the historical significance of the Silk Road, exploring how it facilitated trade, cultural exchange, and the dissemination of ideas across continents and how it continues to influence the modern world.

The Origins of Silk: A Chinese Innovation

The Silk Road owes its name and much of its historical significance to the invention of silk production in ancient China. Legend attributes the discovery of silk to the Chinese Empress Xi Lingshi during the reign of the Yellow Emperor, around 2677 to 2597 B.C.E. The process of sericulture involved raising silkworms (Bombyx mori) and cultivating mulberry trees to feed them. These remarkable creatures spun cocoons with long, strong, and luxurious silk filaments, which could be unwound and woven into fabric.

The secret of silk production was closely guarded by the Chinese for centuries, making it a coveted commodity. Silk’s remarkable qualities, including its breathability, insulating properties, and lustrous appearance, contributed to its popularity in clothing, religious rituals, and as a medium for artistry and trade. Silk was so highly regarded that it was used to pay taxes and salaries during various Chinese dynasties.

The Spread of Silk Along the Silk Road

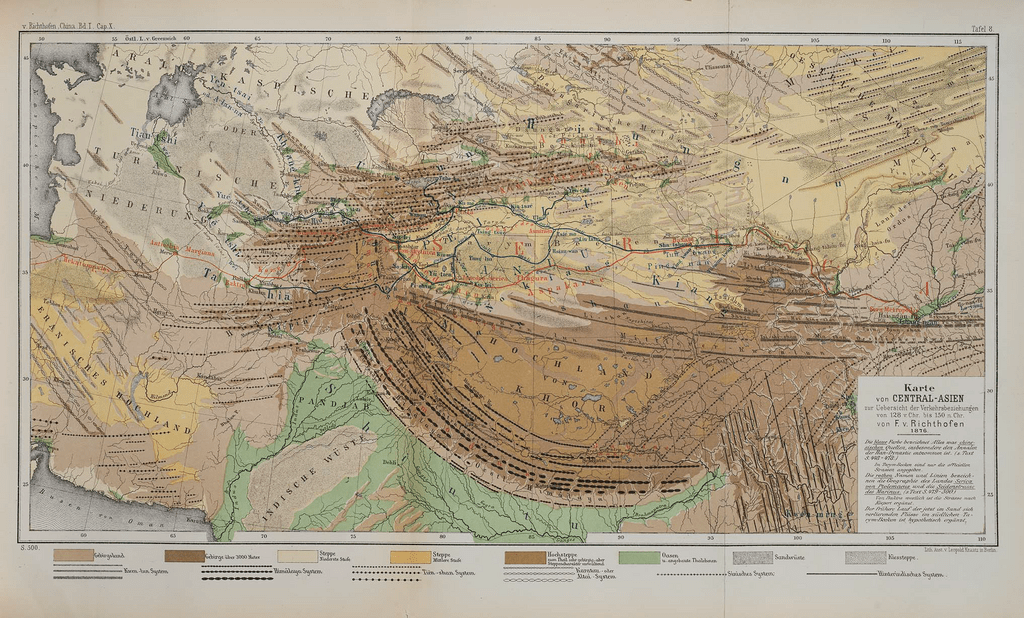

While the Chinese were the first to produce silk, its appeal quickly transcended borders. Evidence of silk trade along the Silk Road dates back to around 500 B.C.E., with strands of silk found in archaeological excavations in Central Asian Bactria, near present-day Afghanistan. Silk also reached ancient Egypt around 1000 B.C.E., although it may have been of Indian, rather than Chinese, origin. The historical record shows that silk trade with the Mediterranean world became prominent during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.).

One significant development was the establishment of the first “Silk Road” when silk from China made its way to Rome, initiated by the Han Dynasty’s treaties with Central Asian peoples. Pliny the Elder, a Roman scholar, mistakenly believed that silk was produced from the down of trees in Seres, which was the Roman term for the area associated with silk production. This precious fabric quickly gained popularity among Romans, leading to a surge in silk imports. Silk became synonymous with wealth and luxury, with Roman elites adorning their clothing with silk strips.

The Tang Dynasty (618-907 C.E.) ushered in a golden era of the Silk Road, characterized by robust trade between Tang China and regions including Central Asia, Byzantium, the Arab Umayyad and Abbasid empires, India, and Persia. This period saw not only the exchange of goods but also a rich interchange of artistic styles, religions, and knowledge.

Cultural Exchange Along the Silk Road

The Silk Road was not just a conduit for trade but also for cultural exchange of unparalleled richness. Various civilizations along the route borrowed and adapted techniques, designs, and motifs, creating a vibrant tapestry of cross-cultural influences.

Chinese silk weavers, influenced by Sogdian, Persian, and Indian patterns and styles, incorporated elements like the Assyrian tree of life, beaded roundels, and bearded horsemen on winged horses into their designs. Byzantines drew inspiration from Persian motifs, adopting the two-headed eagle as their symbol and weaving the Tree of Life into their textiles. Japanese weavers developed tie-dye and resist dyeing techniques for their kimonos. This cultural cross-pollination enriched artistic traditions and contributed to the global heritage of art and craftsmanship.

Religions and ideologies also traveled the Silk Road. Buddhism spread from India through Central Asia to Tibet, China, and Japan, while Islam was carried by Sufi teachers and armies across the continent. Martial arts, sacred arts like calligraphy, and various other forms of knowledge were transmitted along with goods, further deepening the cultural connections.

The Mongol Silk Road and Marco Polo

The Mongol Empire, spanning from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean, facilitated a third phase of Silk Road trade during the 13th and 14th centuries. The Mongols, with their continental dominance, ensured a period of relative peace known as the Pax Mongolica, fostering economic and cultural exchanges.

The Venetian explorer Marco Polo, who embarked on a journey that lasted 24 years, played a pivotal role in introducing Europeans to the wonders of the Silk Road. Polo’s tales of his travels, narrated while he was imprisoned in a Genoese cell, ignited European interest in the Silk Road region. He described the vast treasures of Asia, from China’s riches to the wonders of the Mongol Empire.

With Polo’s accounts and other European discoveries, the Silk Road captured the European imagination. It played a vital role in stimulating the age of exploration, as explorers sought safer and cheaper sea routes to Asia to secure the valuable commodities found along the Silk Road.

The Silk Road and the Modern Era

In the modern era, the Silk Road continued to exert its influence, particularly in the realm of trade and culture. European cities like Lyon, Venice, and Genoa became hubs for silk production and trade, while Paris emerged as a center for silk fashion. The development of the Jacquard loom in 1804 revolutionized silk production, enabling mass manufacturing of intricate patterns. European designers drew inspiration from Asia, creating their versions of Chinese and Turkish motifs, sparking a fascination with Orientalism.

The industrialization of silk production, coupled with advancements in synthetic dyes, led to the proliferation of silk textiles. Silk became not only a symbol of luxury but also a medium through which cultures connected and influenced each other. The international appeal of silk fashion, furnishings, and other products demonstrated the enduring legacy of the Silk Road in shaping global aesthetics and commerce.

Central Asia and the Silk Road Today

In the contemporary era, Central Asia has regained significance on the world stage. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the ensuing political changes have repositioned the region as a crossroads of competing interests and ideologies. The U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, the discovery of oil reserves, and the development of pipelines have renewed focus on Central Asia’s geopolitical importance.

Nations in the region are striving to build stable economies, infrastructures, and social institutions. Efforts are underway to revive traditional craftsmanship, such as Uzbek ikat weaving, and to celebrate the region’s rich cultural heritage. The Silk Road’s legacy continues to inspire contemporary artists, designers, and musicians, leading to a resurgence of interest in Central Asian culture.

Conclusion

The Silk Road stands as a testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and the power of cultural exchange. For over two millennia, this intricate network of trade routes facilitated the movement of goods, ideas, and cultures across vast distances. Silk, the iconic product of the Silk Road, served as both a commodity of economic value and a symbol of civilization and sophistication.

The Silk Road’s historical significance extends.